Since over a decade the omnipresent SOA architecture and ESBs were considered a state of the art when it comes to integration architecture. Still there are lots of organizations where ESBs is in use. If you still have an ESB as a main hub of your integration stack, it is probably time to start considering som newer options. The world moved on and “agile” has also reached the integration architecture.

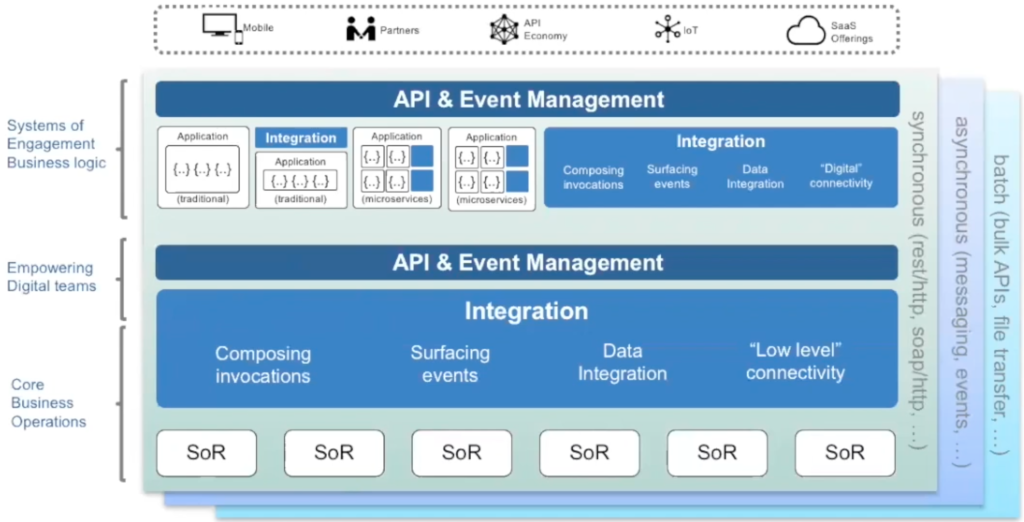

But before we look at what agile integration is, we need to take a broader look on the integration architecture. An example of that could be the the reference architecture model shown below (Based on IBM Think 2018 presentation: http://ibm.biz/HybridIntRefArch).

The integration architecture patterns ar often divided into three main categories: synchronous, asynchronous and batch integrations. Synchronous integrations are often implemented as http/https or ReST interfaces, asynchronous integrations are mostly different kinds of pub-sub or streaming integrations and finally batch are often referenced to as ETL (Extract Transform Load) or more recent ELT (Extract Load Transform) and are very commonly used in connection with data warehouses, various dataplatforms and data lakes.

With the on march of the cloud technologies, the integration architecture has also more an more adopted cloud as the execution environment and there seem to emerge two main streams on how the integrations are being implemented in the cloud: either as the native PaaS or the “best of suite” iPaaS /iSaaS type of plattform.

The native PasS basically uses the very basic components in one or more of the major PaaS plattforms (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) Here we talk about components like f.eks. AWS API GW, AWS Kinesis, AWS SNS/SQS, AWS Step Functions, Azure API Manager, Azure ESB, Azure Logic App and so on. The “best of suite” iPaaS/iSaaS is basically a complete integration suite implemented as a SaaS service e.g. like Dell Boomi, Informatica or MuleSoft which often provide a set of adapters for different protocols.

The integration architecture has also evolved over last decade from the infamous centralized SOA architecture and ESB to a more distributed architecture. This evolution has happened and affected three different axises: people, architecture and technology.

In the architecture and technology axis, as the development becomes more and more autonomous, with cloud services, big data and micro service oriented architecture as well as the new ways of running software natively in cloud or in containers, also the integration architecture developed into a more distributed variant. The centralized ESB like plattforms disappear, the integration became either of the point to point type for synchronous integrations or pub-sub and high performance streaming for asynchronous integrations. The integration software itself became more distributed and in some cases also run either in containers or natively in cloud.

Finally as the integration is more distributed and often developed by separate autonomous teams, it is also natural that different integrations are implemented using different technologies and programming language or become what we call polyglot integrations.

Another consequence of this evolution in the integration architecture are changes affecting the people axis. With autonomous teams and distributed integrations there is no longer need for centralized integration teams and the integration resources are now spread over different teams. This means as well that the integration architecture becomes more of a an abstract aspect that has to be taken care of in the organization, often without resources that are explicitly allocated for this task and often without clear ownership. This trend basically follows the same pattern as for the other dimensions of the enterprise architecture including security and information architecture.

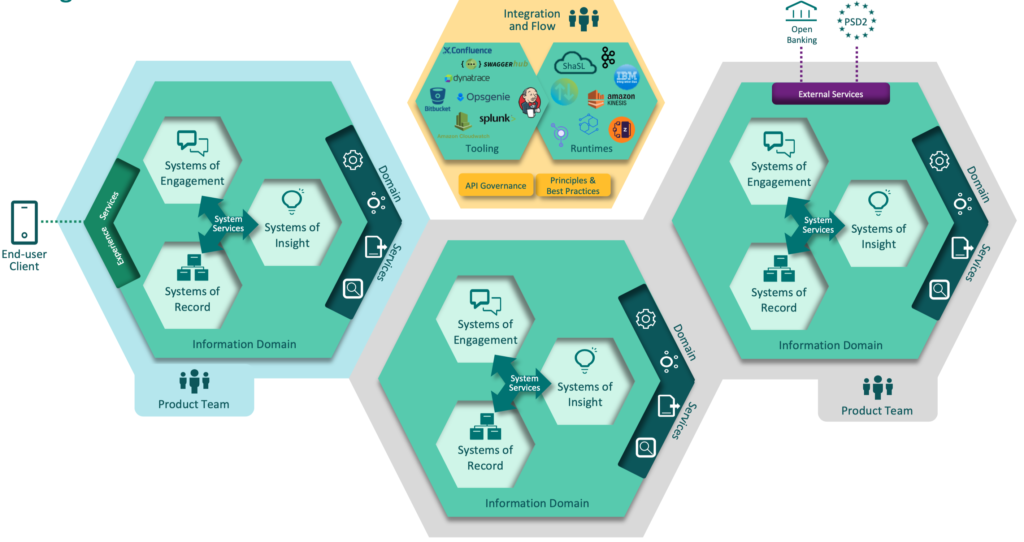

The integration architecture also follows another important trend, called domain driven architecture (DDD). DDD is another force that pushes integration architecture from centralized and layer oriented architecture into a more distributed architecture with more tight integrations inside each domain and more loosely coupled integrations with other domains and external services. This makes it possible to reduce complexity of long technical value-chains with unnecessary transformations, increases the ownership of integration artifacts as well reduces the amount of overlapping data that pops up everywhere. Here is an example of Domain Centric Integration Architecture at DNB (presented at IBM Think Summit Oslo 2019)

Process orientation is another important aspect in particular when looking at the digitalization as the process improvements and optimization are possibly the most important areas for driving any business to be more digital. Also integrations need therefore to become more process driven instead of being only technology driven. However the traditional, centralized integration plattforms give little space for adjustments and adaptation to better facilitate the changes in processes and make it therefore difficult to tailor the integrations to fit the improvements in the processes. As the choice of platform is often purely technology driven, once the plattform is selected and implemented it is usually hard to adapt to the actual process. If lucky, the chances are that you have wide enough range of adapters and tools to fit your needs, but there is no guarantee to that.

Cloud based “À la carte” integration platform, where one can pick the most suitable integration components and only pay for the components in use and for the time they are in use, are therefore more suited for process driven integration approach.

The critics would however point out that with the rise of the modern, distributed, autonomous and polyglot integration plattforms we lost some of the important capabilities that e.g. SOA and ESB provided. The integrations are becoming more point-to-point and with that adding more complexity and increase the “spaghetti factor”. There is no longer one place, one system, which hides the complexity and where you can look and see how your portfolio is integrated and see all dependencies. In practice this is not such a big issue and can be solved by either documentation, reverse engineering or self-discovery mechanisms and there are several tools that make this task easier. The point-to-point challenge can also be alleviated e.g by using data lakes and data streaming mechanisms that reduce the need for direct point-to-point integrations, just to mention Sesam (https://sesam.io/) or Kafka (https://www.confluent.io/)

On the other hand one could point out that the new plattforms no longer support several aspects of the traditional ESB VETRO pattern which stands for Validate, Enrich, Transform, Route and Operate (https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/enterprise-service-bus/0596006756/ch11.html)

This is somewhat correct, however with distributed, conteinarized and polyglot integrations it is relatively easy to implement all necessary validations, enrichments and transformations. When it comes to routing, there are several components which can provide similar functionality in Azure (APIM) or AWS (API GW) and also the Operate aspect is more of a task of the autonomous DevOps team that operates the service with its integrations.

Summarizing, the integration architecture has undergone massive changes in several dimensions and evolved from the centralized SOA/ESB platform into a more distributed, autonomous and polyglot architecture. This development has been catalyzed by underlying trends in IT development and architecture, in particular, DevOps and autonomous teams, digitalization and process orientation, cloud, microservices and containerization of the architecture. The result is the integration architecture, which is more flexible and more adaptable both when it comes to the business needs, but also needs of the development organization itself and finally the rise of what we call Agile Integration architecture.

This work excluding photos and pictures is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.